The Meaning of Emotional Tears

“Where words fail, tears speak.”

Why do we cry?

What is the meaning of tears?

At first glance, the answer seems obvious. Tears protect the eye. They lubricate, clean, and defend it from pathogens. But this explanation quickly falls apart when we look at emotional crying. Crying from sadness, grief, or even joy does nothing obvious to protect the cornea. And yet, humans do it frequently, intensely, and often in social contexts.

This mystery already troubled Charles Darwin.

In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Darwin tried to trace every emotional expression back to a functional ancestor. Showing teeth is threatening because it originally preceded a bite. Disgusted facial expressions mirror the motor patterns of expelling bitter or toxic substances. Over and over, Darwin found a bodily action that once had a clear physical function and later became an emotional signal.

But when he reached tears, he got stuck. He devoted an entire chapter to crying and reached no conclusion. Emotional tears seemed to have no obvious functional antecedent. They were not protective, not preparatory, not instrumental. For a long time, this made emotional crying look like a strange evolutionary leftover, perhaps uniquely human and socially symbolic but biologically inert.

That view has started to change.

What are tears, biologically speaking?

Tears are not just salty water. They are complex biological fluids produced by the lacrimal and accessory glands, containing proteins, peptides, lipids, metabolites and electrolytes. Their composition seems to change depending on context.

Traditionally, we distinguish three types:

- Basal tears, continuously secreted to keep the eye healthy

- Reflex tears, triggered by irritants like smoke or onion vapors

- Emotional tears, triggered by strong affective states

For a long time, emotional tears were considered special mainly because of their psychological and social meaning in humans. However, research in rodents showed that tear fluid, regardless of emotional context, can act as a chemical signal and influence social behavior.

Rodents: tears as chemical signals

In mice, tears have been shown to carry chemosensory signals that modulate social interactions. Several studies have demonstrated that tear fluid contains peptides capable of altering behavior, including sexual receptivity and aggression. Some tear-borne molecules enhance reproductive behaviors, while others suppress inter-male aggression, depending on sex and physiological context.

Crucially, female mouse tears contain signals that reduce inter-male aggression. When male mice are exposed to female tear cues during social encounters, their aggressive behavior drops, and activity in brain regions controlling aggression is altered.

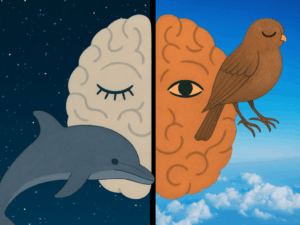

In rodents, these effects are largely mediated by the accessory olfactory system. Humans, however, do not have a functional equivalent of this system. For a long time, this made researchers assume that similar mechanisms could not exist in our species.

That assumption turned out to be wrong.

Human tears: odorless but not inert

In 2011, a study tested a simple but radical idea: maybe human emotional tears also carry a chemical signal.

Researchers collected emotional tears from women while they watched sad films. Importantly, the tears were perceptually odorless. Men who sniffed them could not consciously distinguish them from saline. And yet, their bodies reacted.

Within 20 to 30 minutes, men who sniffed women’s emotional tears showed a significant reduction in free testosterone, the biologically active fraction of the hormone. Brain imaging revealed reduced activity in regions associated with sexual arousal, including the hypothalamus.

From hormones to behavior: aggression

More than a decade later, a follow-up study asked a sharper question: what is the behavioral meaning of this effect?

The answer was unexpected but consistent with rodent data. Men exposed to women’s emotional tears behaved less aggressively in controlled laboratory tasks. At the neural level, the tears altered connectivity between olfactory regions and brain networks involved in aggression.

This suggests a possible evolutionary function that Darwin could not see: emotional tears may act as a chemical signal that inhibits aggression in others.

Not a signal we consciously perceive, but one that our biology still responds to.

Are all emotional tears the same?

Here the story becomes incomplete.

All human behavioral studies so far used negative emotion tears, typically sadness. Tears of joy were not tested. One practical reason is simple, according to the principal. investigator of these studie: sadness tears are easier to collect in sufficient quantities. A sad movie can reliably induce prolonged crying in many people. Joy tears are often brief and unpredictable.

Chemical studies suggest that tears produced during different emotional states do not have identical compositions. But no study has yet shown that only sadness tears carry the behavior-modulating signal, or that joy tears lack it.

So at present, we cannot say whether the effect is specific to sadness, to emotional tears in general, or to something else entirely.

Open questions

Despite the progress, many questions remain unanswered:

- Do tears of joy have similar, weaker, or opposite effects?

- Do men’s emotional tears carry comparable signals?

- Is there a single active molecule, or is the effect produced by a mixture?

- Does this mechanism operate in real-life social interactions, or only in laboratory settings?

What we can say is that emotional tears are not just symbolic expressions.

Evidence suggests that they can act as biologically active social signals, reducing aggression and potentially serving a protective function.

Darwin could not identify a functional antecedent for emotional tears, but contemporary research is helping to clarify their biological role.

📖 References:

- Female mouse tears contain an anti-aggression pheromone. Zilkha, N., Liron, T., Midzyanov, T. B., & Dantzer, R. Scientific Reports, 2020.

- A chemical signal in human female tears lowers aggression in males. Agron, S., de March, C. A., Weissgross, R., Mishor, E., Gorodisky, L., Weiss, T., Furman-Haran, E., Matsunami, H., & Sobel, N. PLOS Biology, 2023.

- Human tears contain a chemosignal. Gelstein, S., Yeshurun, Y., Rozenkrantz, L., Shushan, S., Frumin, I., Roth, Y., & Sobel, N. Science, 2011.

- Human tears contain a chemosignal that alters testosterone. Oh, T. J., Kim, S., Kim, Y. J., Kwak, E., & Kang, J. PLOS ONE, 2012.

- Why We Cry & the Evolutionary Purpose of Tears. Sobel, N., & Huberman, A. YouTube, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WfP8AQRcP-g