Living at the Speed of a Tic: Tourette Syndrome

“Tourette syndrome is an excess of nervous energy, of impulsion, with a strange production of movements and utterances” – Oliver Sacks

Few clinical stories illustrate this description better than Witty Ticcy Ray, a chapter from The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, in which Oliver Sacks recounts the case of a man whose life unfolded at an accelerated neurological pace.

Ray had Tourette syndrome from the age of four. His body produced sudden motor and vocal tics: rapid, involuntary movements and sounds. In his case, the condition extended beyond tics alone. Marked impulsivity, explosive energy, and episodes of aggression affected his relationships and cost him several jobs.

Yet that same neurological intensity shaped his talent as a jazz drummer. His improvisations were fast, unpredictable, and rhythmically complex. While playing, the same neural intensity that disrupted his daily life shaped his rhythm.

When treated with haloperidol, a dopamine-blocking drug, his tics diminished. But so did his speed, spontaneity, and musical vitality. For someone who had never known life without Tourette syndrome, the medication felt like a transformation of identity, not just symptom control. Eventually, Ray found a compromise: medication during the workweek for stability, and drug-free weekends to reclaim his creative energy.

His story illustrates a central tension in neurology: when we modify brain chemistry, we are not only suppressing symptoms, we are reshaping patterns of personality and expression.

What Happens in the Brain of a Person with Tourette Syndrome?

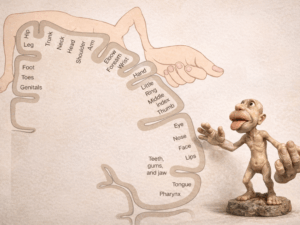

Tourette syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder involving dysfunction in circuits that connect the frontal cortex and the basal ganglia.

These circuits regulate motor control, impulse inhibition, habit formation, and the filtering of competing actions. Under normal conditions, inhibitory mechanisms suppress irrelevant motor programs. In Tourette syndrome, this inhibitory gating is impaired, allowing unwanted movements and vocalizations to break through.

Dopamine appears to play an important role. In many patients, the brain circuits that rely on dopamine, particularly within the basal ganglia, seem to be overactive or overly sensitive. This may explain why medications that reduce dopamine signaling, such as haloperidol, can reduce the intensity of tics.

But Tourette syndrome is not simply a matter of “too much dopamine.” The brain is not governed by a single chemical. Other systems involved in inhibition, including GABA and glutamate, also contribute. Brain imaging studies show that patterns vary from person to person.

Rather than a single imbalance, Tourette syndrome reflects a broader difficulty in regulating inhibition. The neural “brakes” that normally suppress unwanted movements are less efficient, allowing impulses to manifest.

What are the causes?

The causes are multifactorial:

- Genetic vulnerability: family studies show strong heritability, though no single gene is responsible.

- Neurodevelopmental factors: subtle alterations in brain maturation likely precede symptom onset.

- Environmental influences: prenatal stress, infections, or perinatal complications may contribute in predisposed individuals.

Furthermore, Tourette syndrome is frequently associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and major depressive disorder. In many cases, these comorbidities impair quality of life more than the tics themselves.

More Than a Movement Disorder

Tourette syndrome was first described in 1885 by Georges Gilles de la Tourette. After initial medical interest, attention gradually declined. The condition was often misunderstood or subsumed under broader psychiatric classifications. It did not disappear; rather, scientific focus shifted elsewhere.

Recognition expanded again in the second half of the twentieth century, particularly from the 1970s onward. The founding of the Tourette Association of America in 1972 marked a turning point, increasing public awareness, advocacy, and research support.

Today, Tourette syndrome is understood not as a curiosity, but as a disorder of neural inhibition affecting motor, cognitive, and emotional regulation.

Ray lived at a pace imposed by his neurological condition. Treating him meant slowing that speed, but also negotiating which aspects of his temperament would remain.

The deeper neuroscientific lesson is this: the brain does not merely generate symptoms. It shapes who we are.

📖 References:

- Sacks, Oliver. (1985). The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales.

- Johnson, Kara A., et al. (2023). Tourette syndrome: Clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology, 22(2), 147–158.