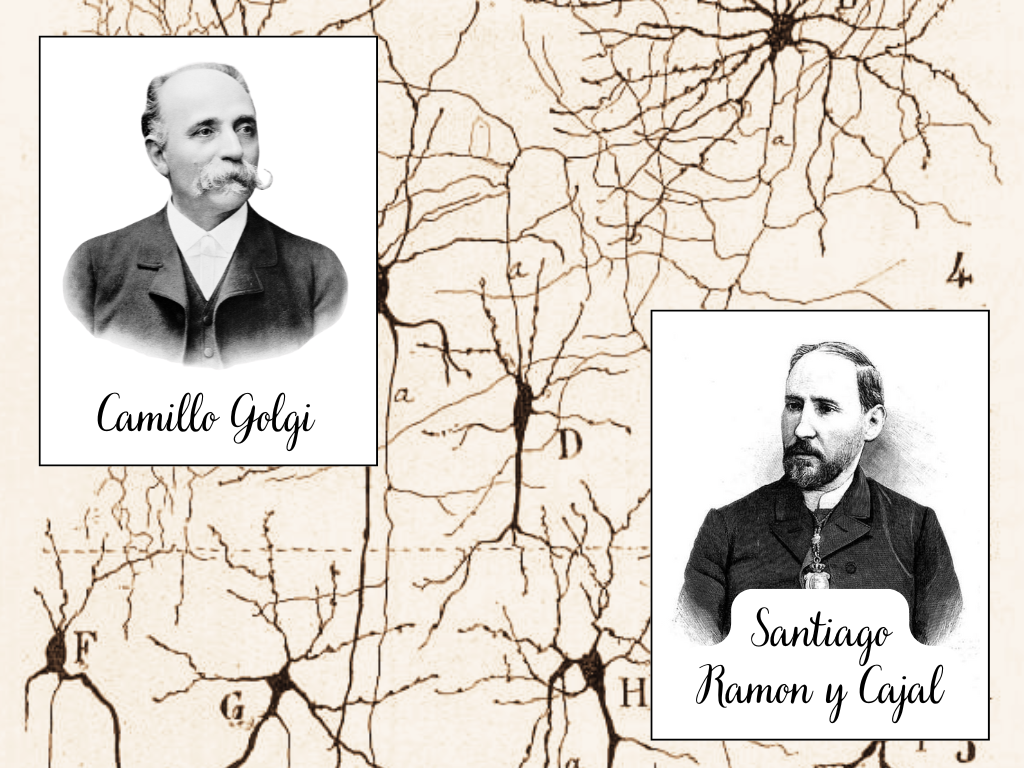

The discovery of Neurons: Camillo Golgi, Santiago Ramon y Cajal and the Birth of Neurobiology

“The nervous system is made up of neurons, independent cells which communicate with one another by contact, not continuity” – Santiago Ramon y Cajal

At the end of the nineteenth century, one thing was clear: the body is made of cells.

Muscles, skin, liver, blood, all could be broken down into individual microscopic units, each with a specific role. The brain, however, remained an exception.

Under the microscope, nervous tissue looked dense and chaotic. It was not possible to see where one cell ended and another began.

There were two main reasons for that:

1) Fresh brain tissue is extremely soft, making it difficult to cut into thin sections without destroying it.

2) Even when slices could be prepared, the available stains barely penetrated the dense connective tissue and myelin that surround nerve fibers.

What researchers saw instead was a thick forest of filaments, overlapping in every direction.

From these observations emerged the so called “Reticular theory”.

According to this theory, the nervous system was not composed of individual cells, but of a single continuous network, a dense mesh in which all elements were fused together. Signals was thought to flow freely through this web.

Among the supporters of this idea was an Italian physician Camillo Golgi.

The black reaction

In 1873, Golgi made a discovery that would change neuroscience forever. He developed a new histological technique later known as the “Black Reaction”.

By immersing brain tissue in two chemical solutions (potassium dichromate followed by silver nitrate), Golgi produced a chemical reaction that filled some nerve cells with dark silver crystals, suddenly revealing their full shape under the microscope.

The result was extraordinary.

For the first time, entire neurons could be seen: the cell body, branching dendrites, and long axons stood out sharply against a light background.

These images were unlike anything scientists had ever observed.

How the black reaction worked?

The Golgi method had a peculiar property: it stained only a small fraction of neurons, apparently at random.

Although the basic chemistry of the reaction is understood, scientists still cannot predict which neurons will be labeled and which will remain invisible.

In a few neurons, local conditions are just right for the first silver crystals to form. Once this initial step, known as “nucleation”, begins, the crystals continue to grow inside that neuron, gradually filling it completely. Nearby neurons may never start this process and therefore remain unstained.

What initially seemed like a flaw turned out to be a gift. If every neuron had been stained, the brain would have appeared as an indecipherable black mass. Instead, the Golgi method revealed individual neurons in striking isolation, making it possible to study their structure in unprecedented detail.

Golgi himself, however, interpreted these images in a particular way. Although neurons could be seen individually, he believed that their axons ultimately fused into a continuous network. In his view, the brain was still one vast reticulum, and dendrites played mainly a nutritional role rather than a communicative one.

Santiago Ramon y Cajal: An artist with a microscope

A few years later, in Spain, a young histologist encountered Golgi-stained tissue for the first time. His name was Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

Cajal was not only a scientist but also an exceptional artist. He trained himself to observe with obsessive precision, and when he looked through the microscope, he drew exactly what he saw. His drawings are among the most famous in neurobiology.

When Cajal began using the Golgi method, he noticed something that others had missed. The darkly stained neurons did not merge into one another. Their branches ended freely. Axons approached other cells closely, but they did not fuse.

Cajal refined Golgi’s technique, adjusting fixation times and working with young and embryonic tissue, where myelin had not yet formed. With these improvements, he obtained images of breathtaking clarity allowing him to confirm that neurons are separate entities.

The birth of the neuron doctrine

From these observations, Cajal proposed that the nervous system was composed of individual neurons that communicate by contact, not continuity. Information flows in a preferred direction, from dendrites to cell body to axon, a principle he later called dynamic polarization.

This idea directly contradicted the reticular theory and placed Cajal in open opposition to Golgi.

Over time, further evidence accumulated. Even though synapses had not yet been directly observed, other scientists proposed their existence to explain communication between neurons. Cajal’s discoveries were later synthesized into what became known as “The Neuron Doctrine“.

The sheared Nobel Prize

In 1906, Golgi and Cajal shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on the structure of the nervous system.

It was an awkward pairing: during their Nobel lectures, Golgi defended the reticular theory, while Cajal presented compelling evidence for the individuality of neurons. Although Golgi acknowledged the directionality of nerve signals, he never fully abandoned his belief in continuity.

History would eventually settle the debate. With the advent of electron microscopy in the mid-twentieth century, synapses were directly visualized and neurons were shown to be separate cells. Cajal was right. Yet the Nobel Prize was equally deserved: Golgi gave the world a tool that made neurons visible, while Cajal gave the world the understanding needed to interpret them. With these two scientists, modern neurobiology was born.

📖 References:

- De Carlos, J. A., & Borrell, J. (2007). A historical reflection of the contributions of Cajal and Golgi to the foundations of neuroscience. Brain Research Reviews.

- Glickstein, M. (2006). Golgi and Cajal: The neuron doctrine and the 100th anniversary of the 1906 Nobel Prize. Current Biology.