How Does Your Brain Know Where Your Body Is In Space?

“She had lost, with her proprioception, the foundation of her body’s identity.” –

Oliver Sacks

How can you touch your nose with your eyes closed?

How can you clap your hands in the dark?

How does your body know and feel where your limbs are in space without relying on vision?

This ability is called proprioception, sometimes referred to as our “sixth sense”.

Whereas the five known senses (vision, hearing, touch, taste, and smell) provide information about the external environment, proprioception allows us to perceive information about our internal state. It continuously monitors the positions and movements of the limbs as well as force production. In other words, it allows us to know where our body parts are located in space and helps stabilize and protect the body.

Since proprioception operates mainly in an unconscious way, we rarely appreciate it until it is disrupted. When this happens, coordination, balance, and motor control can deteriorate significantly.

But how does it actually work?

Mechanisms Underlying Proprioception

Proprioception arises from the coordinated activity of many specialized mechanosensory neurons, collectively called proprioceptors, located in muscles, tendons, joints, and the skin. Together, they encode different aspects of body mechanics, giving the brain a rich and reliable picture of limb position and movement.

Four main groups contribute most clearly to proprioception:

- Muscle spindle

These are tiny, coil-like structures located inside muscles. They run parallel to the muscle fibers and measure how long the muscle is (muscle length) and how quickly it is stretching or shortening (movement speed). Muscle spindles are the reason you can sense whether your arm is bent or straight, or how fast you are lifting something.

- Golgi tendon organs

Found where muscles connect to tendons, these receptors measure how much force the muscle is producing. They help you judge how heavy something feels when you pick it up and automatically adjust the force of your grip or movement.

- Joint receptors

Located within the joint capsules, these receptors sense the angle between bones and detect when a joint is approaching the limits of its normal range of motion. They help refine movement and protect joints from excessive stretching.

- Skin mechanoreceptors

The skin also contributes: stretch-sensitive receptors in the skin provide information about limb posture and movement. When you move, the skin deforms in specific patterns that reflect the position of the joints underneath. Remarkably, skin stretch can still provide positional information even if deeper receptors are damaged.

Unlike other senses like vision or hearing, which rely on a specific organ, proprioception works by integrating signals from muscles, tendons, joints, and skin to build a coherent sense of body position. It also works together with vision and the balance system of the inner ear. All these signals are blended to give the brain the most accurate possible estimate of where the body is in space.

From Body to Brain: How Proprioception Is Processed

Proprioceptive receptors send their information through sensory nerves into the spinal cord. From there, the signals travel to two main brain areas.

- One major pathway goes to the cerebellum, located at the back of the brain. The cerebellum is responsible for the unconscious understanding of our body’s position. It helps coordinate movement, maintain balance, and make rapid corrections when something destabilizes us. All of this happens automatically, without conscious awareness.

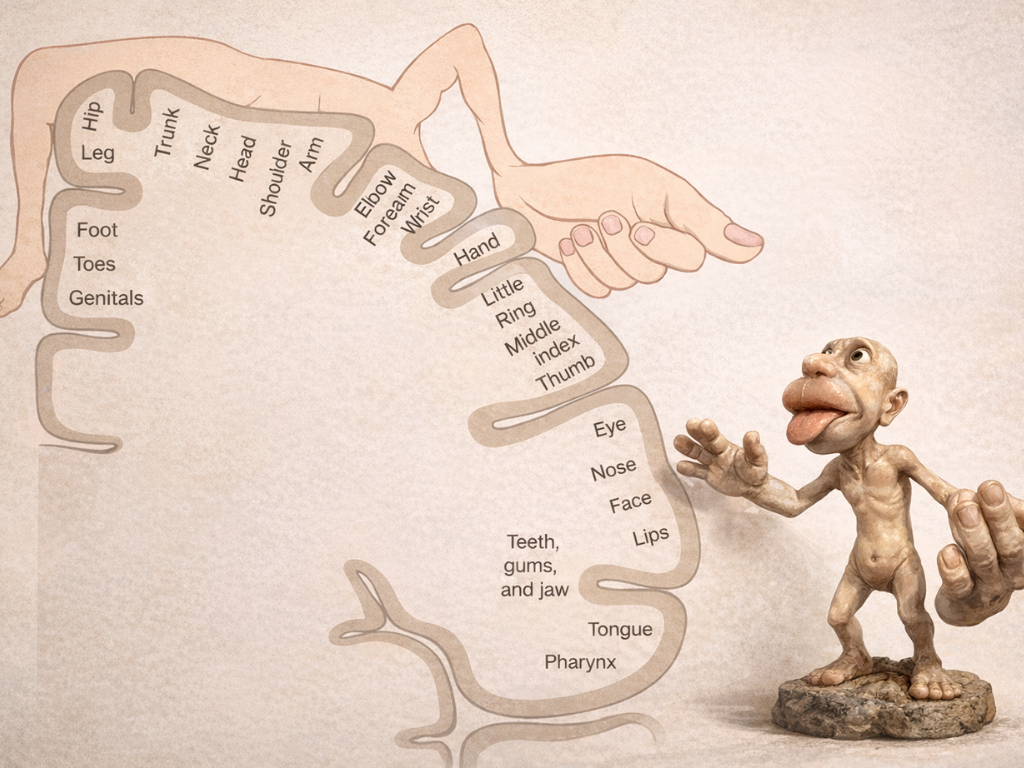

- Another pathway goes to the somatosensory cortex in the parietal lobe. This region creates our conscious map of the body’s position. Different body parts are represented here, and some, such as the hands and face, occupy proportionally larger areas because they require finer control and greater sensitivity.

Here, proprioception is combined with vision, touch, and input from the vestibular system. Together, these signals allow the brain to construct a unified sense of where the body is relative to the external world.

What Can Impair Proprioception?ì

Proprioception depends on three key components: 1) the sensors in our muscles and joints, 2) the nerves that carry their signals and 3) the brain regions that interpret them. When any of these systems are altered, our sense of body position becomes less accurate.

Among other factors, aging, fatigue, and alcohol, growing up and injuries affect proprioception in clearly noticeable ways.

- Aging: With age, proprioceptive receptors gradually lose sensitivity, nerve conduction slows, and the brain regions involved in balance and body awareness become less efficient. These changes make movements less precise and increase the risk of falling.

- Fatigue: When muscles are tired, their internal sensors respond less accurately to stretch and force. At the same time, both spinal and cortical processing slow down. This is why coordination often deteriorates when we are exhausted.

- Alcohol: Alcohol suppresses the cerebellum, the brain region responsible for unconscious proprioceptive integration, and slows neural communication throughout the nervous system. The result is unsteady movement, delayed reflexes, and impaired balance.

- Growing up: During childhood and adolescence, rapid changes in body size and limb proportions require the brain to continuously update its internal body map. During these growth phases, proprioception can be temporarily less precise.

- Injuries: Injuries such as ligament damage can disrupt proprioceptive signaling by damaging mechanosensory receptors in joints and connective tissue. As a consequence, altered or unreliable information may be sent to the brain, which can impair movement control and increase the risk of re-injury if not properly compensated.

Role of proprioception on phantom limb syndrome

When a limb is amputated, the physical limb is gone, but the brain’s map of that limb remains. The brain has spent decades receiving proprioceptive information from that limb, so the representation does not disappear immediately. The brain may continue sending motor commands to the missing limb and expect proprioceptive feedback in return. Because no signals arrive, the brain experiences a mismatch, which can lead to the vivid sensation that the limb is still present.

Over time, the cortical areas representing the missing limb may reorganize, a process called cortical remapping. For example, in some amputees, touching the face can evoke sensations in the phantom hand because those regions lie adjacent in the somatosensory map. Mirror therapy takes advantage of this plasticity to reduce phantom limb pain by providing the brain with visual feedback that replaces the missing proprioceptive signals.

Proprioception is so seamless that we rarely notice it, yet it underlies every movement we make.

📖 References:

- The Proprioceptive Senses: Their Roles in Signaling Body Shape, Body Position and Movement, and Muscle Force. (2012). Proske, U., & Gandevia, S. C. Physiological Reviews, 92(4), 1651–1697.

- Alcohol: effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. (2007). Oscar-Berman, M., & Marinković, K. Neuropsychology Review, 17, 239–257.

- The perception of phantom limbs: The D. O. Hebb lecture. (1998). Ramachandran, V. S., & Hirstein, W. Brain, 121(9), 1603–1630.