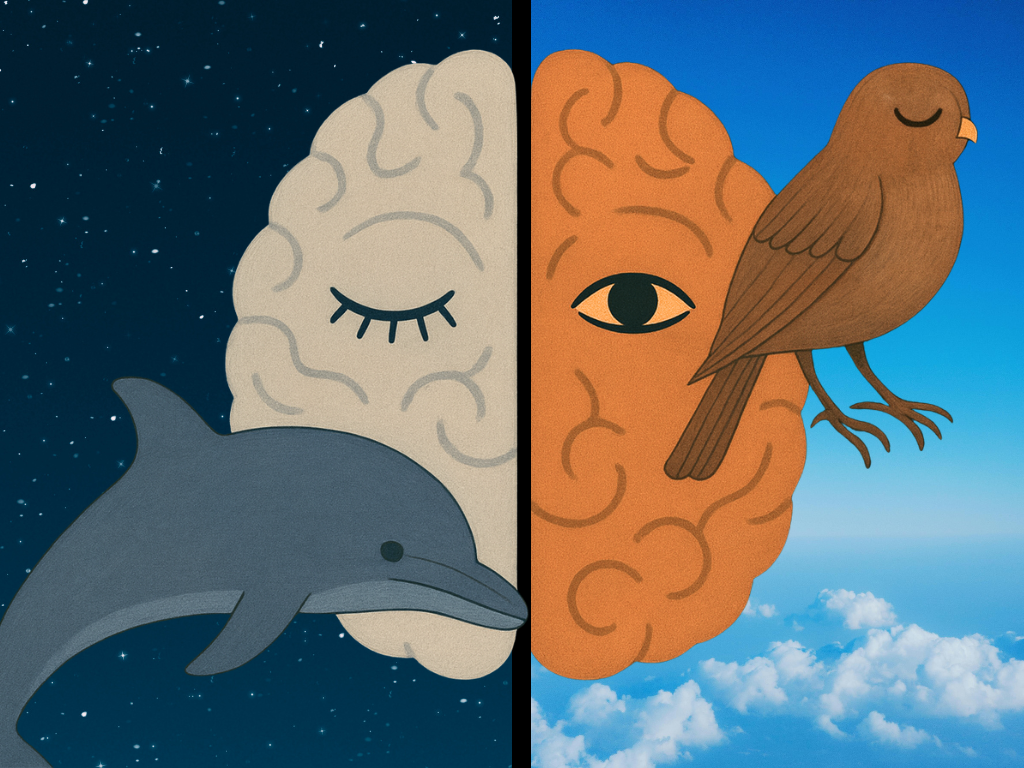

Sleeping With Half a Brain: Birds and Dolphins Do It

“Each night, when I go to sleep, I die, and the next morning, when I wake up, I am reborn“ – Mahatma Gandhi

Tigers can sleep for about 15.8 hours per day, while horses sleep only around 2.9 hours. Humans sleep with both hemispheres of the brain working in synchrony, but some animals like birds and dolphins can sleep with only half of their brain at a time.

From an evolutionary point of view, the fact that all animals sleep suggests that sleep must serve an essential biological function. However, sleep duration and sleep strategies vary dramatically across species.

To understand how and why some animals can sleep with only half of their brain, and thus rest while remaining alert, we first need to understand how sleep works.

Types of Sleep: NREM and REM

Until the 1950s, people thought sleep was a passive, almost coma-like state. This changed in 1953, when Eugene Aserinsky and Nathaniel Kleitman used electroencephalography (EEG) to show that brain activity during sleep is not uniform.

EEG measures the electrical signals from groups of neurons, which appear as wave-like patterns. “Not uniform” means that these patterns change in amplitude and frequency during the night.

EEG patterns correlate with characteristic eye movements, which are closely tied to cognitive processes like thinking, recalling or imagining. The two main phases identified during sleep were classified based on eye movement and are known as NREM (Non-Rapid Eye Movement) and REM (Rapid Eye Movement). REM is the stage most strongly linked to dreaming.

These two types of sleep repeat roughly every 90 minutes. As the night goes on, deep NREM sleep becomes shorter, while REM periods get longer.

NREM sleep is divided into four stages (NREM 1, 2, 3, and 4), which increase in depth, with stages 3 and 4 being the deepest, and hardest to wake from.

When entering NREM sleep, heart rate slows, body temperature drops, and eye movements decrease significantly. Then, during REM sleep, eye movements become rapid, brain activity becomes highly active, and muscles become almost completely paralyzed, likely to prevent people from acting out their dreams.

Why two phases, and why a cycle?

A leading explanation is that NREM helps clear unnecessary neural connections, while REM strengthens important ones. Together, they create a biological “cleaning and reinforcing” cycle. Furthermore I guess that if someone slept only very briefly, they might get little or no REM sleep.

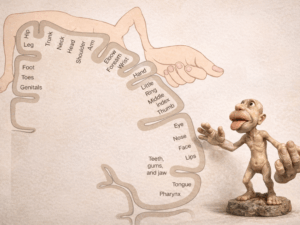

When humans sleep, both hemispheres go through these phases together, showing symmetrical activity—except in one particular and curious situation that I will mention at the end of the article. Some animals, however, can sleep with one hemisphere while the other stays awake. This is called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep, also known as asymmetric sleep.

Uniemispheric slow-wave sleep

Unihemispheric slow-wave sleep (USWS) is a remarkable ability found in several species where one brain hemisphere sleeps, entering deep NREM slow-wave sleep (only NREM, there is no REM phase), while the other hemisphere stays awake.

The eye opposite to the awake hemisphere remains open, while the other eye closes.

EEG recordings show slow-wave sleep (typical of deep NREM sleep) on one side and wake-like activity on the other. The hemispheres alternate their roles so each side eventually gets rested.

Most birds and many marine mammals, such as dolphins and whales, use unihemispheric sleep. However, there is an important difference: dolphins must sleep this way, while birds use it only when needed.

Birds

Asymmetric sleep is widespread in birds but not universal, and it is not used all the time. Many birds rely primarily on normal bilateral sleep (both hemispheres asleep), especially in safe environments. However, they can use unihemispheric sleep in situations that require vigilance, such as detecting predators, or maintaining stability while like perching or during sustained flight. A study on great frigatebirds (Rattenborg et al.) showed that while migrating over the ocean for days without landing, they can enter very brief episodes of symmetric sleep (with both hemispheres asleep), all while soaring on stable rising air currents that allow them to remain in the air.

When birds use bilateral sleep, they can experience REM sleep (so they probably dream?). However, REM episodes in birds are very short (typically a few seconds).

Cetaceans (Dolphins, Whales, and Some Seals)

Unlike birds, cetaceans must sleep unihemispherically to survive.

In fact, dolphins, for example, are conscious breathers, meaning they must remain partially awake to surface and breathe. If both hemispheres slept simultaneously, they would fail to surface, which would be fatal. Like birds, they also keep one eye open during unihemispheric sleep, which provides some vigilance against potential predators. Another important factor is thermoregulation: because water accelerates heat loss, dolphins need to keep moving (even very slowly) continuously to maintain body temperature.

Unihemispheric sleep allows them to rest while still swimming, breathing, and monitoring their surroundings.

As a result, dolphins experience only NREM-like unihemispheric sleep and are thought not to enter true REM sleep or dream. They swim slowly while one hemisphere sleeps, and after 1–2 hours the hemispheres switch roles. This pattern repeats many times per day, allowing them to obtain rest while maintaining the functions necessary for survival.

What about human? do they never experience Unihemispheric sleep?

Unihemispheric sleep is not known to occur in humans. However, when people spend their first night sleeping in an unfamiliar environment, their sleep is often disturbed, a phenomenon called the “first-night effect.” Researchers (Tamaki et al.) studied brain activity during this night and showed that the left hemisphere remained more vigilant than the right.

This functions as a sort of internal “night watch,” somewhat analogous to asymmetric sleep in animals, though far less pronounced.

Basically, in humans, both hemispheres sleep, but one sleeps a little less deeply.

PS:

These explanations are not exhaustive. Each species, and even each group within a species, can have its own sleep patterns and strategies shaped by ecological pressures and social behavior.

📖 References:

- Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. (1953). Aserinsky, E., & Kleitman, N. Science.

- Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. (2017). Walker, M.

- Night watch in one brain hemisphere during sleep associated with the first-night effect in humans. (2016). Tamaki, M. et al. Current Biology.

- Unihemispheric sleep and asymmetrical sleep: Behavioral, neurophysiological, and functional perspectives. (2016). Mascetti, G. G. Nature and Science of Sleep.

- Evidence that birds sleep in mid-flight. (2016). Rattenborg, N. C. et al. Nature Communications.